Time, Scale and "Systems thinking" for philosophy

Two important concepts

I have been reading Dominic Cumming’s substack recently and have picked up the term “systems thinking” from his writing. This is a way of thinking where we examine a subject as an entire system and understand the ways various pieces of the system are related. An example from his blog is how in WWII the British general lord Alan Brooke understood how the different fronts of France and Italy were related to one other. This was in contrast to many of his peers who examined particular fronts on there own without understanding how action in one front impacted the other. This way of thinking is helpful in all kinds of domains, whether it be business, engineering or war. In this blog I want to talk about how we can apply that way of thinking to philosophy. Understanding what the major components of our “philosophical system” are and how various ideas might impact them will improve our thinking and hopefully improve discussions in the public discourse.

In my previous post on free will I used systems thinking without explicitly labelling it as such. There was an argument by some who wanted to do away with the concept of free will as they claimed it was illogical. By understanding how free will impacted other areas of philosophy like our choices around legal responsibility, we came to understand that the denial of free will was simply a bad argument. Those who were denying free will were simply focused in on one particular area, the supposed tension with deterministic physics. Just as some of the generals around lord Alan Brooke couldn’t understand how military decisions in Italy impacted events in France, our free will deniers were not able to understand how there argument led to an overall more incoherent worldview. “Systems thinking” in philosophy starts with the goal of a coherent worldview, one that allows an individual to navigate life and hopefully bring about good in society as well as to themselves.

Whenever we hear new political or philosophical arguments we should be applying this way of thinking. Not just arguing about minute details at random but understanding how arguments fit into our overall system of philosophy. Two of the most important concepts to understand in this systems view of philosophy are time and scale.

When we consider how a given philosophical/politic argument impacts our system of philosophy we need to keep in mind our stated goal from above, navigating life in such a way that we bring about good to society as well to ourselves. Time is a crucial piece of our philosophical system to evaluate ides. We want to take a given idea and play it out over long time scales. You can think of long time scales as the gatekeeper for good ideas because they force a given philosophy to solve certain specific problems if they are going to survive. The first of those hurdles is the fact that human beings are mortal but ideas are not, so a philosophy must be able to find new followers.

An idea that simply dies out in one generation cant claim to bring good to society as it won’t last long enough to do so. For an idea to “survive” it has to have people who believe in it. At long time scales, say 200+ years, an idea will live longer than any of the actual people who believe it. So for an idea to survive it must be able to be passed on from generation to generation. If an idea can’t get anyone from the younger generation to buy in then it will simply die out. So long time scales help filter out any ideas that don’t have some mechanism for transmitting values to the younger members of society. If we look at ideas that have managed to survive for a long time we can see that they have evolved these mechanisms. Religions often have baptisms, confirmations, or other initiation rites. Most longstanding political parties have some kind of youth org to help get younger people in the party. The specific mechanisms may vary but they have to be there or the idea will simply fade away over time.

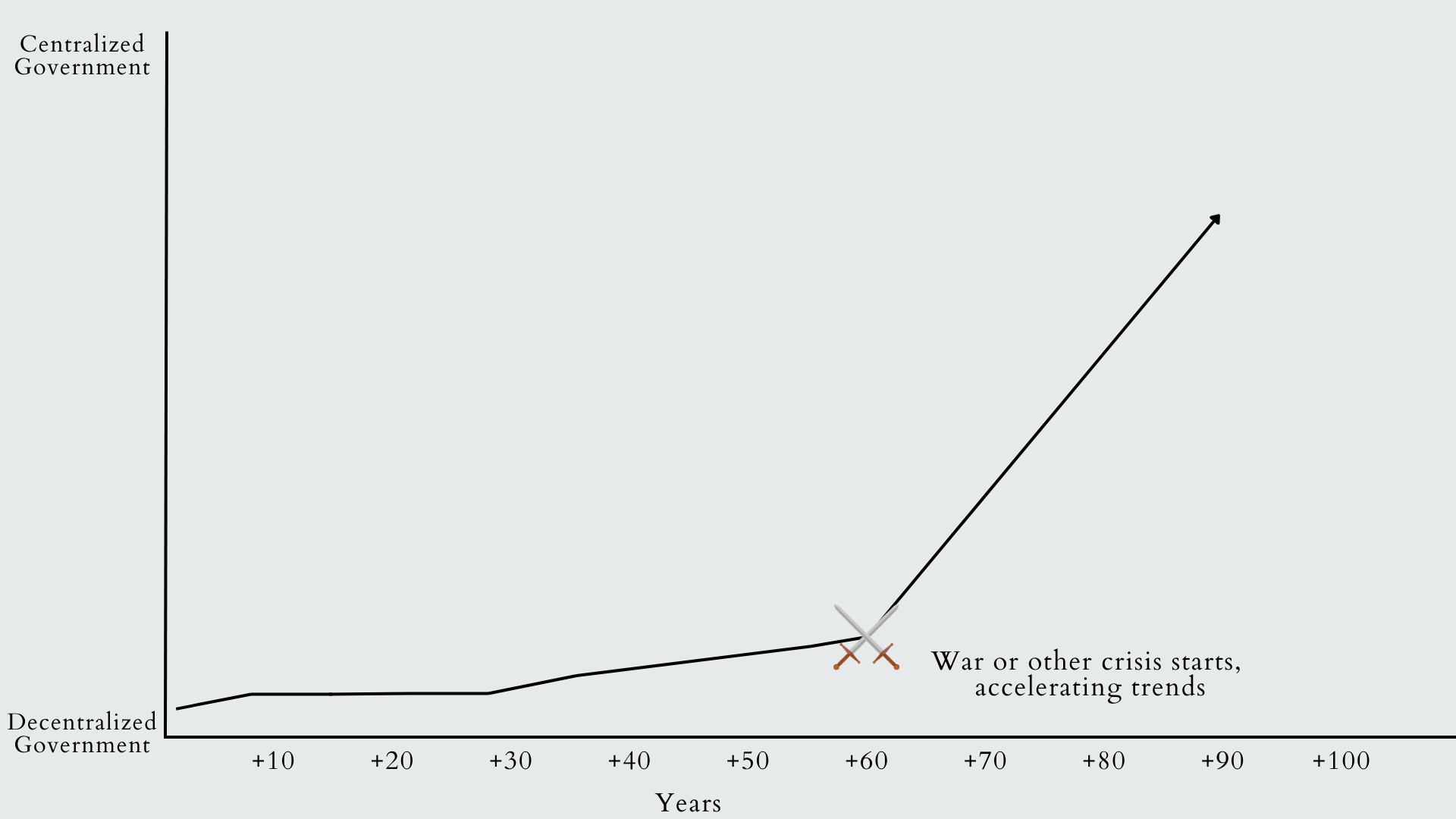

Society’s inevitably face crisis’s and problems that they must overcome. These might be wars, economic issues or even natural disasters all of which must be overcome by the current political regime. If the crisis is not resolved, the regime along with there philosophy of how to rule, will be replaced by some other regime that is more capable of fixing the crisis. In actual history it does not always work out so cleanly that philosophy X gets immediately replaced by philosophy Y due to a failure to resolve a specific crisis. But if we look at various societies such as America, Russia, France we can see that throughout there history they have changed under the weight of multiple crisis’s. If a philosophy recommends that society be organized in a specific way then that recommendation must be able to survive the crises and problems that society’s inevitably face. At long time scales the probability that some crisis will arise increases to the point of certainty. So society’s must have the ability to respond and overcome these challenges or they will not survive. They must also have the difficult task of being able to respond to these problems in such a way that they don’t abandon there philosophy in the process. Anarchism is a trivial yet classical example of a philosophy that can not pass this test. If a group of anarchists were able to actual create an anarchist area then they would have to maintain that over time. At long time scales there is a high probability that either some outside group would infringe on there anarchy or some members of the anarchist group would give up on the philosophy. So an anarchist would have to come up with strategies to overcome these problems. The problem is that any strategies to resolve these problems would require organization from the anarchists that would inevitably lead to the recreation of government. So the idea of anarchism couldn’t survive at long time scales because the survival strategies to survive over long time scales contradict the philosophy itself. Time helps illustrate that societies are not static, they do not have qualities and beliefs that simply persist. Society’s are always growing, shrinking, changing in some way or direction. Using long time scales helps us understand how certain ideas will cause a society to change over time. If those changes and forces converge over time to undesirable outcomes then we can reject the idea based on those flaws.

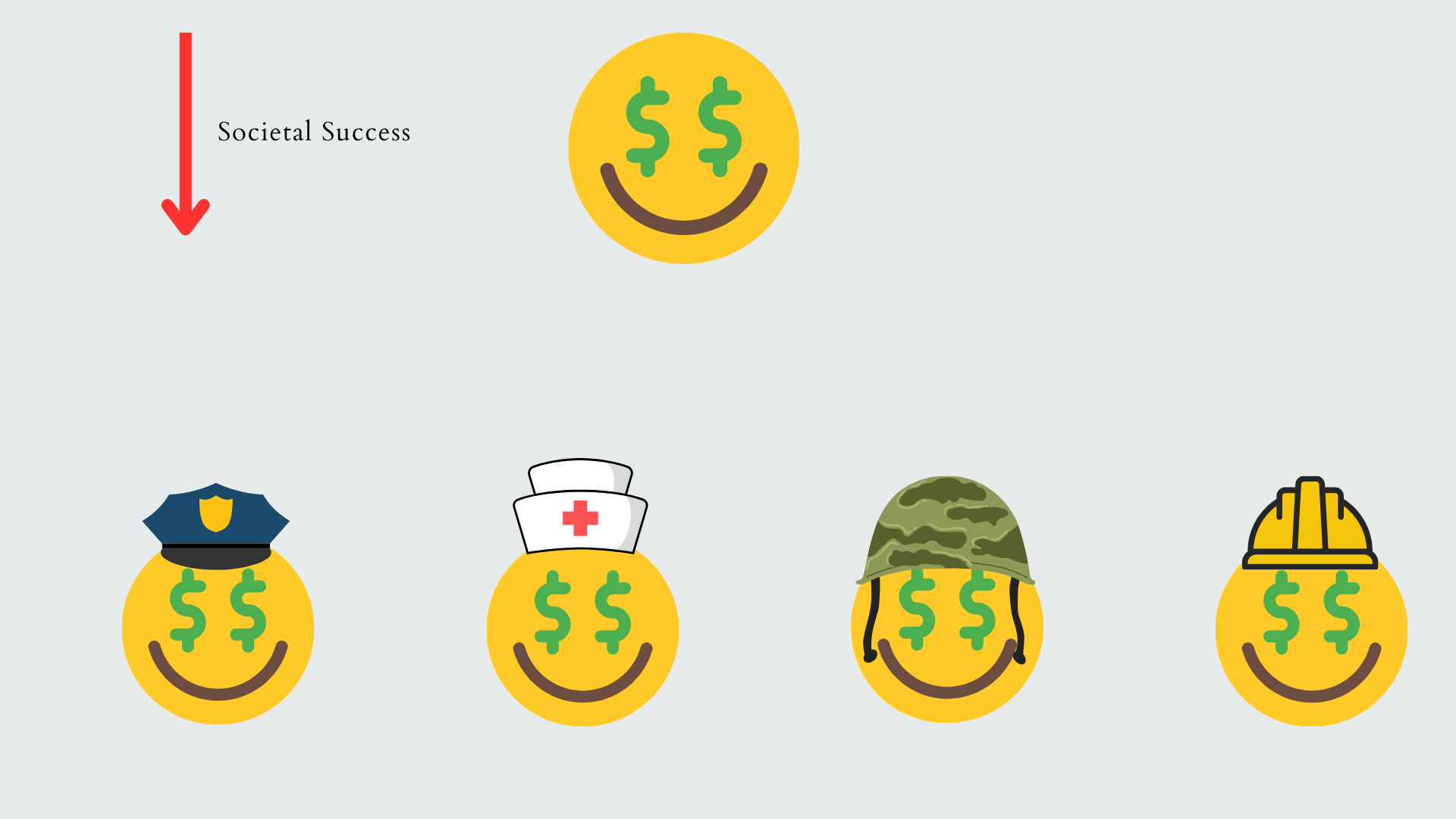

The second import concept to understand in our system of philosophy is scale. Philosophies start as something that is individual in nature, one person has a way of thinking about the world. As they share that idea, more and more people can begin to believe it and act it out. Some philosophies work well at an individual level but don’t work well at the societal level. When we talk about scale we are referring to the number of people acting out said philosophy. As an example you could imagine someone who is totally selfish and ruthless would excel in the corporate world. There prioritization of themselves at all costs would cause them to raise up the ranks, they would make money and benefit socially from the prestige of a high up position. From the individuals perspective it seems like a sound philosophy that only brings good things to them. But it is of course fundamentally limited, one person behaving selfishly might work but that can’t scale up, a society were every human being was ruthlessly selfish couldn’t function and would be a terrible society to live in. Imagine a world where every doctor, every police officer, school teacher, mother, father was only looking out for themselves. Societies are networks of individuals that are all reliant on each other for success. If the network as a whole ceases to function then so does the individual embedded in it. A selfish existence wouldn’t scale even if it worked at a individual level.

When other nodes in the social network are still contributing its possible for one individual node to take advantage and gain a relative advantage to there peers.

But if significant portions of the network pursue the same goal then the network itself collapses and all individuals fail.

There are less nefarious examples that still fail to scale. Someone might believe for instance that the best most effective and most altruistic thing for them to do would to become a billionaire and give all there money to charity. This idea while far less nefarious than our selfish corporate example is also flawed when we scale it up. If everyone spends there time acquiring money and trying to give it to charity, who would do the work at all the charities acquiring the money? If the goal is to donate money to a given charity that does say medical charity then there would still need to be some amount of doctors, nurses who are simply doing there job and not trying to pursue a life as a billionaire philanthropist. Practically seeking we don’t even need to have the “everyone in society follows a philosophy” examples for us to see the effects of scale. Even if the top 10% of the most competent people in a given field or business pursued an unscalable philosophy the results would be visible in society.

Keeping time and scale in our focus when evaluating an idea will improve our thinking. It helps us avoid the attention related issues that we discussed in my last post. These ideas are not particularly ground breaking, they are in fact blatantly obvious. The hard part is not forgetting them when we get involved in some emotional argument. This is the key to systems thinking in philosophy, keeping our attention on the big picture and understanding how a given idea impacts it. I will investigate applying the systems view of philosophy to more ideas in future blog posts.